Q: What do you do when your library book has been eaten by a bear?

A: Make a new one, of course!

It’s not the set-up to an elementary school joke, really, but the plight of some poor, hapless monk who lived all the way back in the twelfth century. What do you do when the book you’re supposed to be taking care of, the really precious one that you were allowed (as a special favor) to take out to an isolated spot to pray over and study, gets snuffled down in two gulps as an ursine snack? This situation — and an utterly charming self-portrait by an eleventh-century monk who called himself “hugo pictor” (Hugh the Painter) — together formed the inspiration for my children’s picture book, Brother Hugo and the Bear, coming out from Eerdmans Books for Young Readers this April. I wrote about the book-munching bear mentioned in a twelfth-century letter of Peter the Venerable in my author’s note at the end of Brother Hugo, but the secret-behind-the-story is that there’s another Brother Hugo . . . a real one. And his part in inspiring our book hasn’t yet been told.

I love studying history. Not the kind of history that people usually think of — the long lists of dates, memorization of “important” battles, or who ruled after whom after whom after whom — but the kind of history where you suddenly run across something that grabs you up and shouts in your ear: “Hey! This is real! I’m real, and I lived and breathed and got hungry, just like you.”

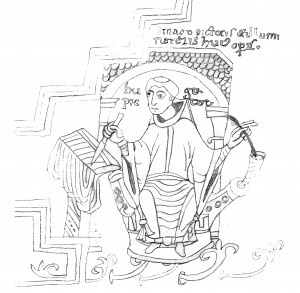

That’s what I felt when I ran across Hugo pictor for the first time. He tucked himself away into a corner of the end of a manuscript (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Bodl. 717, fol. 287v) of Saint Jerome’s Commentary on Isaiahover nine hundred years ago — and he’s still there, peering out at us. His is perhaps the oldest known self-portrait by an illuminator, the person whose job it was to “draw the pictures” and occasionally add in the rubricated letters (the “red” or “colored” letters that began pages, sections, or sentences) in medieval manuscripts. Another monk, the scribe, had the responsibility of writing out the words themselves. Many times the same person would both write the words and illuminate the pages, but in our monk Hugo pictor’s case, his representation suggests that he was there just to provide “color commentary” — literally.

In his self-portrait, he sits in a nifty writing chair with a built-in inkhorn rising from the arm, not exactly with his mind on his work. He gazes off into the mid-distance, his blue monk’s robe draped around him, penknife in his right hand hovering over a lined manuscript page on a tilted writing desk, his left hand dipping a quill or a brush into his horn of ink, lost in thought. Is he in the middle of correcting a mistake? Is he holding the page still with his knife while he goes for more ink? With expressive eyebrows, green tonsured hair, and bright spots on his cheeks, he’s absolutely real — and he wants you to know it! Traditional scribal anonymity (and modesty) is not for him. On either side of his portrait, framing his head, he has written: hu — go. pic — tor. Just above, tucked in between the top of his arch and the zig-zag lines he has drawn to separate the text from the rubricated title letters below, he writes: imago pictoris et illuminatoris huius operis “The image of the painter and illuminator of this work.”

This bit of well-deserved pride wasn’t his only self-portrait, either. Hugo also left us with another medieval selfie in part of an illuminated letter “E”, where he shows himself as a priest or a deacon blessing an Easter candle. The figure there is inscribed as “hugo levita” or Hugh the Deacon (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Ms. lat. 13765, fol. B). “E” here stands for

Exultet, the hymn of praise sung during the Easter vigil, and the singer or speaker of this prayer is a prominent person in the Easter ritual. Hugo was apparently just making sure we would know that

he was the one involved, just as he does in the Bodleian manuscript. That’s our boy.

At the Oscars this year, Ellen’s famous selfie crashed Twitter, and Benedict Cumberbatch successfully photobombed the band U2 with his aerial shenanigans. But Hugo pictor outdid them both: he photobombed Saint Jerome’s Commentary on Isaiah, and his epic selfie has stared out at readers for the better part of a thousand years.

The past usually feels so far away, and when you run into it, real and live — and funny — it can be exciting and oh-so-close. That’s what I’m hoping readers of Brother Hugo and the Bear will feel, too.

* The title of this post is an homage to medieval book historian Erik Kwakkel’s amazing tumblr, where he often writes about medieval scribes and illuminators. His post, “Medieval selfie,” features another illuminator/self-portrait artist, the red-headed Brother Rufillus. Erik re-blogged a post by Damien Kempf about our own Hugo pictor in 2013.

This post was originally published as “A Medieval Selfie” on EerdWord, March 13, 2014.