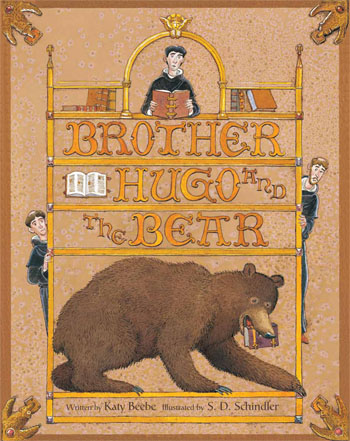

A Junior Library Guild Selection

* Kirkus Reviews Starred Review

A Kirkus Best Book of 2014

A Kirkus Best Book of 2014

*School Library Journal Starred Review

“interesting, wry and educational” — The New York Times

“combines suspense, humor, and information in a handsome, entertaining package” — School Library Journal

Written by Katy Beebe

Illustrated by S.D. Schindler

Eerdman’s Books for Young Readers 2014

It befell that on the first day of Lent, Brother Hugo could not return his library book. The Abbot was most displeased.

“Our house now lacks the comforting letters of St. Augustine, Brother Hugo. How did this happen?”

“Father Abbot,” said Brother Hugo, “truly, the words of St. Augustine are as sweet as honeycomb to me.

But I am afraid they were much the sweeter to the bear.”

The precious book, it turns out, has been devoured by a bear — and so the Abbot tasks Hugo with replacing it. Letter by letter and line by line the hapless monk crafts a new book and sets off to return it. Once a bear has a taste of letters, though, he’s rarely satisfied. With a hungry bear close on his heels, will Brother Hugo ever make it back with his fine parchment in one piece?

Based loosely on a note found in a twelfth-century manuscript, this humorous tale will surely delight readers who have acquired their own taste for books.

ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATOR —

S.D. Schindler is an award-winning illustrator of many bestselling picture books, including Come to the Castle! (Flash Point), The Story of Salt (Putnam Juvenile), and Big Pumpkin (Aladdin). He lives in Pennsylvania. You can visit his website at www.sdschindlerbooks.com.

Click here to read The New York Times review of Brother Hugo and the Bear

***

“Prepare to be charmed by a bear who loves words—or at least loves to eat them.

Brother Hugo cannot return his book to the library of the monastery: A bear has consumed it. Enjoined to go to another priory to borrow a volume that he might copy to replace what the bear ate, he finds the bear follows him, snuffling hungrily. All his brother monks help him to prepare the parchment, make the inks, sew the pages and bind it shut. They even supply him with scraps of text to toss to the bear as Brother Hugo attempts to return the book he had copied. This does not work out, exactly. The rhythm of the text is antique but lucid and sweet, and the pictures, festooned with curlicues and decorated in shades of gold, gray and brown, echo the manuscript illuminations that inspired them. Rich backmatter gives all the historical background without detracting from the essential spark of the tale. The author, who holds a Ph.D. in medieval history, was inspired by a line from the 12th-century abbot Peter the Venerable about a precious volume eaten by a bear to make this lively story.

This accurate (if abbreviated) delineation of the process of medieval manuscript bookmaking shines thanks to the fey twist of ursine longing for the written word.”

— Starred Review, Kirkus Reviews

***

“According to detailed back matter, the author learned of a documented incident involving a book-eating bear and the subsequent letter written by Peter the Venerable to a neighboring French monastery requesting St. Augustine’s letters. That research inspired this story that combines suspense, humor, and information in a handsome, entertaining package. As the tale begins, Brother Hugo confesses his unfortunate loss to the abbot, who asks: “Pray tell, … how did a bear find our letters of St. Augustine?” Hugo replies ruefully, “They seemed to agree with him.” His penance is to journey to Chartreuse to borrow the manuscript and copy it. Beebe’s language creates an Old World flavor, as Hugo “sorely sighed and sorrowed in his heart” and “sped full mightily.” When he begins to copy the borrowed book, the enormity of the task dawns on him, and the brothers offer assistance. Readers then obtain a clear overview of medieval bookmaking, from the stretching and scraping of sheepskin to the laborious copying and binding. Schindler’s elegant compositions make full use of each spread. Text wraps around delicate ink and watercolor brooks and grazing sheep, while illuminated letters decorate and amuse. Arches and columns cleverly frame the monk, creating sequential panels to portray his painstaking progress on what becomes, alas, another “choice morsel” for the insatiable beast. Combine this with C. M. Millen’s The Ink Garden of Brother Theophane (

— Starred Review, School Library Journal

***

““It befell that on the first day of Lent, Brother Hugo could not return his library book.” In a medieval twist on the homework-eating dog, Brother Hugo confesses to his abbot that a bear has eaten his borrowed copy of St. Augustine’s letters. The abbot instructs Brother Hugo to retrieve a copy of the book from a neighboring monastery and create a new version—hand-written, illuminated, and bound. This process forms the heart of debut author Beebe’s how-it’s-done story as Hugo’s fellow monks aid in his efforts. The capital letters of each paragraph are meticulously illuminated in ink and wash by Schindler (Spike and Ike Take a Hike) with small vignettes and ornaments. Beebe’s period prose is believable and at times funny (Brother Hugo “knew that once a bear has a taste of letters, his love of books grows much the more”), and Schindler’s Bruegelesque landscapes deepen the medieval atmosphere. Depending on readers’ temperaments, they’ll either laugh or despair at the ending, in which all of Hugo’s hard work comes to naught.” — Publishers Weekly